ESSENTIAL READING – SPEAKING TRUTH TO POWER – EDWARD SAID

The Basic Question for an Intellectual – How does one speak the Truth? The Reith Lectures, 1993.

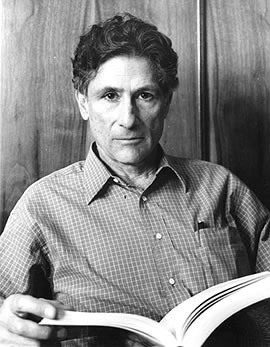

Edward W. Said was born in Jerusalem and raised in Egypt; from 1951 onwards he lived in the United States. He was Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. Said wrote on various subjects, illuminating the gaps of cultural and political understanding between the “Western and the Eastern world”; he is recognised as one of the founders of “Post-colonialism”.

I suggested that as a way of maintaining relative intellectual independence, having the attitude of an amateur instead of a professional is a better course. But let me be practical and personal here.

I suggested that as a way of maintaining relative intellectual independence, having the attitude of an amateur instead of a professional is a better course. But let me be practical and personal here.

In the end, one is moved by causes and ideas that one can actually choose to support because they conform to values and principles one believes in. I do not therefore consider myself bound by my professional training in literature, consequently ruling myself out from matters of public policy just because I am only certified to teach modern literature. I speak and write about broader matters because, as a rank amateur, I am spurred on by commitments that go well beyond my narrow professional career. Of course, I make a conscious effort to acquire a new and wider audience for these views, which I never present inside a classroom.

But what are these amateur forays into the public sphere all about, really? Is the intellectual galvanised into intellectual action by primordial, local, instinctive loyalties – to one’s race, people, or religion – or is there some more universal and rational set of principles that can, and perhaps do, govern how one speaks and writes? In effect, I am asking the basic question for the intellectual: how does one speak the truth? What truth? For whom and where?

Unfortunately, we must begin by saying that there is no system or method broad and certain enough to provide the intellectual with direct answers to these questions.

Take as a starting point the whole, by now extremely disputatious matter of objectivity, or accuracy, or facts. In 1988 the American historian Robert Novick published a massive volume whose title dramatised the quandary with exemplary efficiency. It was called That Noble Dream and subtitled The ‘Objectivity Question’ and the American Historical Profession. Drawing on materials taken from a century of historiographic enterprise in the United States, Novick showed how the very nub of historical investigation – the ideal of objectivity by which a historian seizes the opportunity to render facts as realistically and accurately as possible – gradually evolved into a mass of competing claims and counterclaims. All of them wore down any semblance of agreement by historians as to what objectivity was to the merest figleaf, and often not even to that. Objectivity has had to do service in the Cold War as ‘our’ (ie, American as opposed to Communist) truth; in peacetime as the objective truth of each competing separate group (women, African-Americans, Asian-Americans, gays, white men, and so and on) and each school (Marxist, establishment, deconstructionist, cultural). After such a babble of knowledges, what possible convergence could there be? Novick asks, and he concludes mournfully that ‘as a broad community of discourse, as a community of scholars united by common aims, common standards, and common purposes, the discipline of history had ceased to exist. . . . The professor (of history) was as described in the last verse of the Book of Judges: ‘In those days there was no king in Israel: every man did that which was right in his own eyes.’ ‘

One of the main intellectual activities of our century has been the questioning, not to say undermining, of authority. So to add to Novick’s findings we would have to say that not only did a consensus disappear on what constituted objective reality, but a lot of traditional authorities, including God, were in the main swept away. There has even been an influential school of philosophers – among whom Michel Foucault, the French thinker, ranks very high – who say that to speak of an author at all (as in the author of Milton’s poems) is a highly tendentious, not to say ideological, overstatement.

In the face of this formidable onslaught, to regress either into hand- wringing impotence or into muscular reassertions of traditional values, as characterised by the global neo- conservative movement, will not do. I think that the critique of objectivity and authority did perform a positive service by underlining how, in the secular world, human beings construct their truths, so to speak, and that, for example, the so-called objective truth of the white man’s superiority built and maintained by the classical European colonial empires also rested on a violent subjugation of African and Asian peoples and they, it is equally true, fought that particular imposed ‘truth’ in order to provide an independent order of their own. And so now everyone comes forward with new and often violently opposed views of the world: one hears endless talk about Judaeo-Christian values, Afrocentric values, Muslim truths, Eastern truths, Western truths, each providing a complete programme for excluding all the others. There is now more intolerance and strident assertiveness abroad everywhere than any one system can handle.

The result is an almost complete absence of universals, even though very often the rhetoric suggests, for instance, that ‘our’ values (whatever these may happen to be) are in fact universal. One of the shabbiest of all intellectual gambits is to pontificate about abuses in someone else’s culture and to excuse exactly the same practices in one’s own. For me, the classic case is that of the brilliant 19th-century French intellectual Alexis de Tocqueville, who to many of us educated to believe in classical liberal and Western democratic values, exemplified those values almost to the letter.

Having written his assessment of democracy in America, and having criticised American mistreatment of Indians and black slaves, Tocqueville later had to deal with French colonial practices in Algeria during the late 1830s and 1840s, where, under Marshal Bugeaud, the French army of occupation undertook a savage war of pacification against the Algerian Muslims. All of a sudden, as one reads Tocqueville on Algeria, the very norms with which he had humanely demurred at American malfeasance are suspended for French actions.

Not that he does not cite reasons: he does, but they are lame extenuations whose purpose it is to license French colonialism in the name of what he calls national pride. Massacres leave him unmoved; Muslims, he says, belong to an inferior religion and must be disciplined. In short, the apparent universalism of his language for America is denied, wilfully denied, application to his own country, even as his own country, France, pursues similarly inhumane policies.

It must be added, however, that Tocqueville (and John Stuart Mill, for that matter, whose commendable ideas about democratic freedoms in England he said did not apply to India) lived during a period when the ideas of a universal norm of international behaviour meant, in effect, the right of European power and European representations of other people to hold sway, so nugatory and secondary did the non-white peoples of the world seem. Besides, according to 19th-century Westerners, there were no independent African or Asian peoples of consequence to challenge the draconian brutality of laws that were applied unilaterally by colonial armies to black- or brown-skinned races. Their destiny was to be ruled.

Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, and C L R James – to mention three great anti-imperialist black intellectuals – did not live and write until the 20th century, so what they and the liberation movements of which they were a part accomplished culturally and politically in establishing the right of colonised peoples to equal treatment was not available to Tocqueville or Mill. But these changed perspectives are available to contemporary intellectuals who have not often drawn the inevitable conclusions, that if you wish to uphold basic human justice, you must do so for everyone, not just selectively for the people who your side, your culture, your nation designates are OK.

The fundamental problem is therefore how to reconcile one’s identity and the actualities of one’s own culture, society and history to the reality of other identities, cultures, peoples. This can never be done simply by asserting one’s preference for what is already one’s own: tub-thumping about the glories of ‘our’ culture or the triumphs of ‘our’ history is not worthy of the intellectual’s energy, especially not today when so many societies are composed of different races and backgrounds as to beggar any reductive formulas.

As I have been discussing it here, the public realm in which intellectuals make their representations is extremely complex, and contains contradictory features. But the meaning of an effective intervention there has to rest on the intellectual’s unbudgeable conviction in a concept of justice and fairness that allows for differences between nations and individuals, without at the same time assigning them to hidden hierarchies, preferences, evaluations. Everyone today professes a liberal language of equality and harmony for all. The problem for the intellectual is to bring these notions to bear on actual situations where the gap between the profession of equality and justice, on the one hand, and, on the other, the rather less edifying reality, is very great.

This is most easily demonstrated in international relations, which is the reason I have stressed them so much in these lectures. A couple of recent examples illustrate what I have in mind. During the period just after Iraq’s illegal invasion of Kuwait in 1990, public discussion in the West justly focused on the unacceptability of the aggression, which, with extreme brutality, sought to eliminate Kuwaiti existence.

And as it became clear that the American intention was in fact to use military force against Iraq, the public rhetoric encouraged processes at the United Nations that would ensure the passage of resolutions – based on the UN Charter – demanding sanctions and the possible use of force against Iraq. Of the few intellectuals who opposed both the Iraqi invasion and the subsequent use of largely US force in Desert Storm, none to my knowledge cited any evidence or made any argument excusing Iraq for what it did.

But what I think was correctly remarked at the time was how weakened the American case against Iraq was when the Bush administration, with its enormous power, pressed the UN towards war, ignoring the numerous possibilities of a negotiated reversal of the occupation before 15 January, when the counter-offensive began, and also refusing to discuss other UN resolutions on other illegal occupations and invasions of territory that had involved the United States itself or some of its close allies.

The real issue in the Gulf so far as the US was concerned was oil and strategic power, not the Bush administration’s professed principles. But what compromised intellectual discussion throughout the country, in its reiterations of the inadmissibility of land unilaterally acquired by force, was the absence of universal application of the idea. What never seemed relevant to the many American intellectuals who supported the war was that the US itself had recently invaded and for a time occupied the sovereign state of Panama. Surely if one criticised Iraq, it therefore followed that the US deserved the same criticism? But no: ‘our’ motives were higher, Saddam Hussein was a Hitler, whereas ‘we’ were moved by largely altruistic and disinterested motives, and therefore this was a just war.

Or consider the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, equally wrong and equally condemnable. But US allies such as Israel and Turkey had occupied territories illegally before the Russians moved into Afghanistan. Another US ally, Indonesia, has massacred hundreds of thousands of Timorese in an illegal invasion during the middle Seventies; there is evidence to show that the US knew about and supported the horrors of the East Timor war, but few intellectuals in the US, busy as always with the crimes of the Soviet Union, said much about that. And looming back in time was the enormous

American invasion of Indo-China, with results in sheer destructiveness wreaked on small, mainly peasant societies that are staggering. The principle here seems to have been that professional experts on US foreign and military policy should confine their attention to winning a war against the other superpower and its surrogates in Vietnam or Afghanistan, and our own misdeeds be damned.

For the contemporary intellectual, living at a time that is already confused by the disappearance of what seemed to have been objective moral norms and sensible authority, is it acceptable simply either blindly to support the behaviour of one’s own country and overlook its crimes, or to say rather supinely ‘I believe they all do it, and that’s the way of the world’?

Most, if not all, countries in the world are signatories to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted and proclaimed in 1948, reaffirmed by every new member state of the UN. There are equally solemn conventions on the rules of war, on treatment of prisoners, on the rights of workers, women, children, immigrants and refugees. None of these documents says anything about disqualified or less equal races or peoples. All are entitled to the same freedoms. Of course, these rights are violated on a daily basis, as witness the genocide in Bosnia today. For an American or Egyptian or Chinese government official, these rights are at best looked at politically, not from a consistently moral standpoint. But those are the norms of power, which are precisely not those of the intellectual whose role is at very least to apply the same standards and norms of behavior now already collectively accepted on paper by the entire international community.

Of course, there are patriotism and loyalty to one’s people. And, of course, the intellectual is not an uncomplicated automaton, hurling mathematically devised laws and rules across the board. And, of course, fear and the normal limitations on one’s time and attention and capacity as an individual voice operate with fearsome efficiency. And no one can speak up all the time on all the issues. But I believe there is a special duty to address the constituted and authorised powers of one’s own society, which are accountable to its citizenry, particularly when those powers are exercised in a manifestly disproportionate and immoral war, or in deliberate programmes of discrimination, repression and collective cruelty.

In all these instances the intellectual meaning of a situation is arrived at by comparing the known and available facts with a norm, also known and available. This is not an easy task, since documentation, research, probings are required in order to get beyond the usually piecemeal, fragmentary and necessarily flawed way in which information is presented. But in most cases it is possible, I believe, to ascertain whether in fact a massacre was committed, or an official cover-up produced. The first imperative is to find out what occurred, and then why, not as isolated events but as part of an unfolding history whose broad contours includes one’s own nation as an actor. The incoherence of the standard foreign policy analysis performed by apologists, strategists and planners is that it concentrates on others as the objects of a situation, rarely on ‘our’ involvement and what it wrought. Even more rarely is it compared with a moral norm.

The goal of speaking the truth is, in so administered a mass society as ours, mainly to project a better state of affairs, one that corresponds more closely to a set of moral principles – peace, reconciliation, abatement of suffering – applied to the known facts. This has been called ‘abduction’ by the American philosopher C S Peirce, and has been used effectively by the celebrated contemporary intellectual Noam Chomsky. Certainly in writing and speaking, one’s aim is not to show everyone how right one is, but in trying to induce a change in the moral climate whereby aggression is seen as such, the unjust punishment of peoples or individuals is either prevented or given up, and the recognition of rights and democratic freedoms is established as a norm for everyone, not invidiously for a select few.

Admittedly, however, these are idealistic and often unrealisable aims; and in a sense they are not as immediately relevant to my subject here as the intellectual’s individual performance when, as I have been saying, the tendency too often is to back away or simply to toe the line.

Nothing in my view is more reprehensible than those habits of mind in the intellectual that induce avoidance, that characteristic turning away from a difficult and principled position which you know to be the right one, but which you decide not to take. You do not want to appear too political; you are afraid of seeming controversial; you need the approval of a boss or an authority figure; you want to keep a reputation for being balanced, objective, moderate; your hope is to be asked back, to consult, to be on a board or prestigious committee, and so, to remain within the responsible mainstream; someday you hope to get an honorary degree, a big prize, perhaps even an ambassadorship. For an intellectual these habits of mind are corrupting par excellence. If anything can denature, neutralise and finally kill a passionate intellectual life, it is these considerations, internalised and so to speak in the driver’s seat.

And finally a word about the mode of intellectual intervention. One doesn’t climb a mountain or pulpit and declaim from the heights. Obviously, you want to speak your piece where it can be heard best; and also you want it represented in such a way as to affiliate with an ongoing and actual process, for instance, the cause of peace and justice.

Yes, the intellectual’s voice is lonely, but it has resonance only because it associates itself freely with the reality of a movement, the aspirations of a people, the common pursuit of a shared ideal.

Let’s look at an example. Opportunism dictates that in the West, much given to full-scale critiques of, for instance, Palestinian terror or immoderation; you denounce them soundly, and then go on to praise Israeli democracy. Then you must say something good about peace. Yet intellectual responsibility dictates, of course, that you say all those things to Palestinians, but your main point is made in New York, in Paris, in London, around the issue which in those places you can most affect, by promoting the idea of Palestinian freedom and the freedom from terror and extremism of all concerned, not just the weakest and most easily bashed party. Speaking the truth to power is no Panglossian idealism: it is carefully weighing the alternatives, picking the right one, and then intelligently representing it where it can do the most good and cause the right change.

No comments yet