“THE GRAPES OF WRATH” – John Steibeck

Ma loves the name of her eldest daughter, Rose of Sharon (I think it comes from a psalm) – “Rosasharn” is the way they say it. The choice of this name is a mark of Steinbeck’s genius, a supreme e.g. of the universal in the particular; it says everything about love of family, the yearning for beauty and the strong individuality of this farming mother – It’s the pioneer spirit – keeping the family together.

An amazing book, one of the great books ever written. It is us – humans. But human nature engraved in sharp relief, it is human nature in extremity. Quoting from the book jacket “majestic in its scale and moral vision; an eloquent tribute to the endurance and dignity of the human spirit.”

Steinbeck travelled and lived with the migrant writers then got their story down in 6 months – published in 1939.

In between the narrative are short chapters with an heroic overview of the saga to find work, which reveal the exploitation of the migrants by the banks and monopolies. The journey begins with Dust Bowl Oklahoma and their debt to the banks. The banks force them off their land and homes in order to grow cotton using tractors (this will accelerate the deterioration of the land but there will be interim profit). There are 300 thousand migrants arrived in California to pick the fruit, the association of California farms forces the farmers to pay migrants less than a living wage and this decreases according to the vast proportion seeking work; an agitator is anyone who mentions more money and they are picked off by the law enforces who work with the association. The Californians hate the migrants, because they are scared of them and beacuse they are starving.

The large fruit farmers of the association own the canneries and they bankrupted the small farmers by putting the price of fruit so low that it is not worth the small farmers picking it – they are OK. Beforethey make profit from canned fruit. Having done this they put up the price of the fruit and all produce and any excess is destroyed so that the starving migrants can’t eat it, e.g. piles of oranges soaked in kerosene and pigs slaughtered and burnt.

It’s a shame to have told you this; it is gripping to piece this together for yourself as you go along but I had to because it’s a vivid e.g. of how monopolies work. And it’s good to compare this with Arundati Roy’s description of the havoc wreaked by monopolies and their support by political rulers in India (“Broken Republic”). Nothing changed. Our rulers are still our oppressors. The world is still run for cheap labour and private ownership of its bounty. Our rulers still prefer guns to a fair share; spend profits on violence instead of justice. We in the privileged world don’t always feel it so directly but nothing changed.

“Pray God someday kind people won’t be poor. Pray God someday a kid can eat. And the association of owners knew that someday the praying would stop. And there’s the end.” Steinbeck believed that every step forward by the workers is never wasted, even when he’s pushed back he’s never slipped back quite to where he was; he believed that when there were two men united fear turned to anger. His vision of the world was one in which human kindness could eventually triumph. He said we should fear the time the bombs no longer fell on the market place. Because that would be the time people stopped fighting for justice (c.f. Brave New World).

“- fear the time when Manself will not suffer and die for a concept, for this one quality is the foundation of Manself, and this one quality is man, distinctive in the universe.” Does history bear out his optimism? He was criticised for being sentimental.

I love his characters and that he accepts that you are born with your character and that a man has to do what he has to do. Ma told Tom that whereas most men are what they are, like his younger brother Al, he, Tom was always more; this is a profound observation – to me it means the potential to grow with your experience, to be open to it and up for it – stick your neck out.

The book of the month is Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath” and we decided to launch the library with a showing of the film, starring Henry Fonda and directed by John Ford.

We did this in The Doodle Bar across the road from our studio in Battersea. It was really nice. Prior to going over Tizer had organized people to each bring a dish of food and then there were free drinks at the bar. I was disappointed that mostly the same people came – the ones who get involved, come on demonstrations. The others? I know people need to get home after a long day but is it really a question of habit; they knew of the event for quite some time in advance and could say, yes, I’ll go and if that means I have to make arrangements at home, I’ll do it. It’s so important to engage with the world.

It’s a great film. Henry Fonda wanted that role so badly, he is a hero and all the casting is shrewd, and the sets – the way it looks is graphic and timeless. It succeeds in condensing Steinbeck’s message and it ends at a good point for a film – on a note of optimism.

The advantage of the book is (of course) more words, words that flow and ideas that build. The book has more flexibility over time to connect all the links in the unbroken chain of robbery that defines monopoly. More time to introduce us to the aspirations of all the individual characters who belong to this rich story of human kinship.

The book continues beyond the point where the film stops and though the chances of survival for the family are precarious the pathos of the final scene is unsurpassed in literature.

Comments:

Chiara Salomini – In the book Steinbeck’s language has such a poetic power especially while describing the landscape. There is an attention to details and a strong sensibility also in the movie’s scenes and the fact it is in black and white adds more pathos to the whole story.

The movie starts with a desolate landscape seen from far away where a man is walking on an empty road. There is the same scene towards the very end.

It reminded me of the cycle of life and the human being’s nature seeking their destiny.

Elisabetta Pensa -I really loved the character Ma Joad, she was the matriarch of the family!

Ma Joad must decide which of her worthless possessions to keep and which to leave behind before vacating her farm for the last time. She sorts through a small box of momentos and souvenirs she has acquired over the years. She burns a postcard and a newspaper clipping of Tom’s imprisonment, and other valuable keepsakes which she cannot take with her, giving up parts of her past that are now irretrievably lost.

At the end she holds up two earrings to her ears and wistfully looks at her reflection, thinking back to some unforgotten moments of pleasure.

Ahkoon Khan – Just to be varied… another memorable scene, when the chap from the government is sitting in his car and is telling Muley Graves he must vacate his premises and hands him a piece of paper.

Muley Grave says, “There ain’t nobody gonna push me off my land! My grandpa took up this land 70 years ago, my pa was born here, we were all born on it. And some of of us was killed on it! …and some of us died on it. That’s what make it our’n, bein’ born on it,…and workin’ on it,…and and dying’ on it! And not no piece of paper with the writin’ on it!” As he falls to his knees and grabs a hand full of dirt in his hand, and lets it run through his fingers, and points to the piece of paper in anger.

Reminded me of my dad when he talks about his family land…..

James Emmett – One of my favourite scenes from the film – I haven’t yet read the book – was near the beginning, when the landowner is talking about the reasons and people behind evicting tenants from the land. Excuse after excuse as to why people are having to leave, and the insistence that there is no one person to whom the tenants could complain is, in my opinion, relevant to the financial situation today. Hundreds of mid-level managers of banks and businesses and yet allegedly, nobody that can be, or is willing to be blamed for our current financial predicament.

The entire theme of the film for me can be demonstrated by the construction in the City of London. Every day we hear of record numbers of unemployed and, yet, skyscrapers are continually popping up around the country. Who are these new jobs in these new shiny buildings going to? These is an ever growing gap between rich and poor, with an incessant need for the mega rich to cling onto their riches while continually attempting to make themselves richer – at the expense of the already impoverished, just like the landowners in the Grapes of Wrath. In the case of London job seekers find that the jobs created are created with people already in mind – in order to get a job you need to have had experience, but in order to gain any experience you need to have had a job. A constant vicious cycle demonstrating the power that the mega-rich have over the mega-poor, unskilled workers are forced to take low pay out of necessity.

Incredible story, that I find really relevant today – thanks for showing it, and I look forward to the next instalment

Vivienne Westwood – The great last scene when Tom says goodbye to his mother is the most emotional in the film and will stay in everyone’s heart and soul. Steinbeck exploits the parting to the full by putting his most important message into Tom’s mouth: he will be everywhere because there will always be someone who will fight so that a kid can eat.

Peter Olive – There are moments of humour among the Joad family, which stand out against the film’s backdrop of unease. Grandma and Grandpa Joad manage to make us smile several times, and their deaths are particularly tragic. Forced away from the farm he founded, Grandpa dies not long into the journey. He is buried along the road he hadn’t wanted to travel, receiving the best burial the family can improvise. Grandma does not make it to California either, and her death involves a gruesome pathos. As the family attempt to cross the state border, their vehicle is inspected. Ma Joad protests to police that they are taking Grandma to get medical help, presenting them with her pale and unconscious body. The pretext succeeds, but it is later revealed that shrewd Ma Joad had known that the old lady was dead already. Clutching Grandma’s corpse throughout, Ma had been keeping Grandma’s death to herself, determined to do whatever it would take for her family to reach California. If the men at the road block had known she was dead the family would not have crossed.

Cobalt – I would like to mention the scene where the farm buildings are being destroyed by one of their friends because he was being paid 3 dollars and had to take the work or risk starvation, despite seeming to understand the plight of the people whose homes he was bulldozing. He was portrayed negatively as he was going along with a task he knew was unjust, but continued anyway for personal reward.

Sara Stockbridge – Because the scene where the family leave their home and must get the grandpa drunk to get him into the truck is funny, it made me feel optimistic, as they do, about them going to California. And so later you share their despondency when they find out there isn’t going to be enough work for all the people headed there, and their sadness when Grandpa dies on the journey.

Carlo Fiore – It’s that speech towards the end of the film: ‘ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be everywhere. Wherever you can look, wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready, and when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build, I’ll be there, too.’

Henry Fonda’s mad, intense stare as he delivers it. A sense of resilience and swagger in the midst of adversity.

Ben Westwood – The scene where a man comes to offer work to the migrants.

One of the migrants says that he would like to see the man’s licence for being able to offer work & that he would also like the wage being offered by him to be put down in writing.

He wants this because a ploy of the employers is to offer good wages to a lot of people, then when they all turn up, because there are more people than jobs available the employer drops the wage. Because someone will do the job if you don’t the worker is forced to take the lower wage, which actually is not enough to live on.

When he hears the words of the suspicious man the man offering work tells his passenger in the car who is a policeman that this man is an ‘agitator’. The policeman then says that there was a burglary recently in the area & that the suspicious man looks a lot like the man they are looking for & that this man should come with him.

The suspicious man realises he is being framed & runs away. The policeman tries to shoot him but shoots another woman by mistake.

This scene is memorable to me because this technique of being able to pay poor wages to someone because of the amount of people trying to get the job is exactly the one being practiced today. A lot of unemployment is a very good thing for an employer wanting to make a ‘profit’. The ‘authorities’ have no interest in the ‘rights’ of a person to a fair wage & they can use the ‘law’ or else they can change the ‘law’ to ‘remove’ anybody who threatens their interest.

Ian Kelly – Her face was not soft; it was controlled, kindly. Her hazel eyes seemed to have experienced all possible tragedy and to have mounted pain and suffering like steps into a big calm and…understanding. She seemed to know, to accept, to welcome her position’ Ma Joad is one of the great creations of 20th century literature – the rock at the centre of her family, and the novel – the sort of earth-goddess who can fend off a mugger with a dead chicken (a scene sadly lacking in the movie).

The lights dim, and the screen flickers into its sepia story. The dustbole. The preacher man. Ma Joad. The maverick ex-con (Henry Fonda) rescuing his family – and himself along the way – on an odyssey across the American west to a Utopia that turns out not to exist. It’s sentimental in its way, and dated of course in its acting style, a little theatrical. But it shocks still to see the Dustbowl and the American Depression on film – another America: the curdled dream. And Ma Joad bestrides it as she ought – an Oklahoma Boudicca facing forces she only partly understands.

‘Being a woman is different’ Ma explains in the closing moments of the film, ‘man, he lives in jerks ‘ she says ‘baby born and a man dies, an’ thats a jerk – gets a farm, an’ loses his farm, and that’s a jerk’ But women are different. They continue on in spite of everything ‘Woman, it’s all one flow, like a stream, little eddies, little waterfalls, but the river, it goes right on. Woman looks at it like that’ she says. In the novel, this isn’t quite so near the end. In the film, ma continues into something a little more political. A woman carries on, like a river. So too will the people and the fight for justice. It keeps on flowing. Sometimes we can all do with a Ma Joad.

Tizer Bailey – “We be out by sun-up”. I was absorbed in the wonderfully old-fashioned language, an enchanting way of putting words together, so descriptive.

I loved the scene packing the wagon. Every mattress piled in, tied on, balancing precariously but the wagon looks like the most comfortable way to make the journey like home from home. I would love to be packed up and heading off on such an unknown adventure. Fear and anticipation in everyone’s hearts, they drive towards the promised land of California. The Joad family drugging Grandpa with cough syrup so as not to leave him behind, “I don’t give a hoot or a holler” he wants to stay with his land even if it is just a dust bowl and an empty wooden shack.

Ya Hsin – One very scene that stuck in my mind is when Casy prayed for grandpa. What he said roughly means that grandpa has got no more worries as he is dead, those who really need prayers are living people who are searching for directions.

The journey of the Joad was firstly led by job opportunities. It was a rather passive decision. This family travelled in the hope that they would not only be able to survive, but would eventually enjoy prosperity as well. However, they were disappointed many times from the material point of view.

With the development of the story, we can see how some characters gradually chose their directions autonomously. And here, the direction is not merely the physical road to follow, but the path that paved by the inner light i.e. when Ma allowed other children in the camp to share their food, when Casy volunteered to be arrested, when Tom finally sees himself in the bigger self instead of the tiny ego….

I asked myself “why this has stuck in my mind?”. Perhaps it simply because I am one of the many confused and lost despite the change of times. Hopefully, on the day I die, the sufferings of life will have earned me some truth.

Andy Hulme – THE WHEATPATCH CAMP: The Joad family literally roll into the federal government camp having used up their last tank of gas. They are greeted with kindness and respect by the manager, Jim Rawley, who explains the democratic processes by which the camp is run, by and for the residents. Rawley was played by an actor called Grant Mitchell who normally played senators and judges. With his well fed appearance, aristocratic demeanor and quirky casual attire he seems out of place amongst the ragged, hungry migrants. His hospitable manner and strikingly immaculate white trousers almost led me to expect him to produce tennis rackets and propose Tom Joad a game. Although strange he is extremely likeable and shows firm and effective leadership dealing with the provocation at the camp dance. His chain smoking offers a clue to a reason for this offbeat piece of characterisation. As cast Rawley closely resembles the image of Franklin D Roosevelt, the then President who was seldom seen in public without a cigarette on the go.

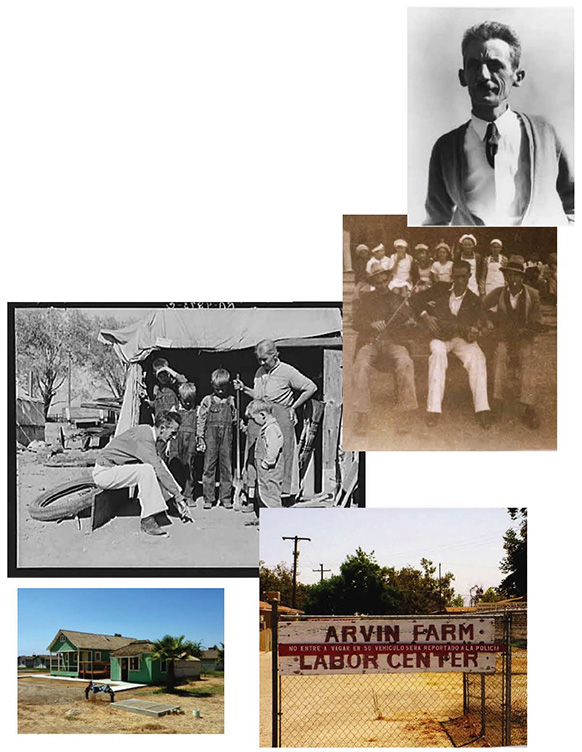

Wheatpatch Camp was based on a real place known as Weedpatch Camp (also called this in the book) or Arvin Federal Government Camp. The real-life manager from its establishment in 1936 was Tom Collins. He acted as John Steinbeck’s guide while he was doing the research which led to Grapes of Wrath and the book was partly dedicated to him. Dorothea Lange took a few photos of him in 1939. A much tougher looking man who wouldn’t have looked out of place in the film. But it turns out he really did wear white trousers. There’s also an amateur photo of “the camp orchestra at Weedpatch” taken three years earlier. It shows a much younger man in white trousers holding a guitar. That must have been Tom Collins too.

Weedpatch Camp is still there. Being restored as a tourist attraction. Nearby is the relocated migrant camp. On the gate a sign in Spanish instructs visitors to report to the police.

Yes, it is a great novel. But let’s give credit to Sanora Babb for the part her, ideas, notes and research played: ‘…in early 1938, [she] began working with the federal government’s Farm Security Administration, traveling the Central Valley with her boss Tom Collins, informing migrants about programs to help them. Each night, she made notes in a journal—fodder for a novel she hoped to publish about the Dust Bowl refugees….Unbeknownst to Babb, Collins was sharing her reports with writer John Steinbeck. By the time she was ready to publish her work, in the winter of 1939, Steinbeck had come out with his own Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, ‘The Grapes of Wrath’. Steinbeck’s book was dedicated to Tom Collins and was an immediate best-seller—such a hit, New York editors told Babb, that the market could not bear another on the same subject….Her Dust Bowl novel, ‘Whose Names Are Unknown’, was published in 2004, the year before her death’.

http://www.pbs.org/kenburns/dustbowl/bios/sanora-babb/

Comment by Anonymous on 29/05/2014 at 3:55 pm