Small Global: Extreme Energy at Glastonbury with Greenpeace

By Natalie Sims and Helle Abelvik-Lawson

As part of a broader display about the effects of climate change on the Arctic in the Greenpeace field at Glastonbury this year, D-Fuse and the Extreme Energy Initiative will exhibit Small Global: Extreme Energy.

Arctic ice, climate change and ‘extreme energy’

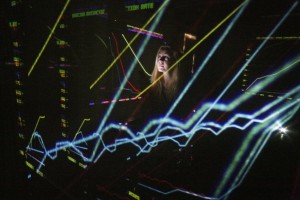

Small Global: Extreme Energy is a collaboration between researchers from the Extreme Energy Initiative (EEI) — based at the Human Rights Consortium, School of Advanced Study (SAS), University of London —and audio-visual artists D-Fuse. The collaboration produced a data-driven installation about climate change, shale gas ‘fracking’, tar sands oil extraction, and consumption — with which audiences are invited to engage directly in an immersive environment of light and sound.

Founded in the mid-1990s by Michael Faulkner and based in London, D-Fuse are an art collective whose work ‘encompasses installations, film, experimental documentary, photography, live cinema performances and architectural projects’ that have increasingly attempted to ‘address social and environmental themes and explore collaborative processes’. The information being presented in the installation complements Greenpeace’s focus for Glastonbury, the Save the Arctic campaign, and associated work on energy and climate change.

Greenpeace is well known for their large-scale naval protest interventions, recently targeting Russian and Norwegian state oil company rigs in the Arctic Circle to stop oil drilling in the region. Arguably, Arctic oil drilling is also a form of extreme energy, which the EEI defines as ‘the process whereby energy extraction methods grow more intense over time, as easier to extract resources are depleted’. As Arctic sea-ice melts, oil prospectors see only vast new fields, thus perpetuating (and accelerating) our greenhouse gas problem – not least because methane release from Arctic sea-ice melt is set to create alarming ‘runaway’ climate change.

With climate catastrophe looming, we cannot lower greenhouse gas emissions by turning to more extreme processes that still produce greenhouse gases. Small Global: Extreme Energy focuses on the extraction processes that are driving climate change, such as:

- The Alberta tar sands, which threaten First Nations’ communities with toxic waste, leading to increased cancer rates and social degradation; and

- Shale gas ‘fracking’, and associated drilling methods such as coal seam gas (CSG) or underground coal gasification (UCG), which have been licenced to take place all over the UK.

The artists describe Small Global: Extreme Energy as ‘an immersive installation that combines data visualisations with high-resolution images and surround sound to address issues of global consumption and environmental degradation’. And it truly is immersive. When it debuted at the Bloomsbury Festival in 2013, it was displayed in the basements of Senate House. Staged in a darkened room across surround-screens, there was nothing to distract the audience from the sounds and sights, and interaction with the installation was encouraged.

The more you engage with the installation, the more information is revealed about the issues being presented. Perhaps the interaction helps to illustrate our involvement in the processes being discussed. Much of the information in the installation is about the relationship between human consumption, environmental degradation and the spread of conflict. By moving about in front of the screens, you change the structure of the installation and what is revealed, just as we change society and the environment by moving through the world. It challenges us to recognise our impact on the planet.

Extreme energy: From global to local impacts

One of the main causes of climate change is the increase in greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere, and emissions from simply extracting substances like tar sands oil are several times higher than those for conventional crude oil. Rising sea levels and an unstable climate affect us all, but unconventional extraction also has devastating local consequences, greatly impacting a wide range of communities from indigenous populations in Canada to people living along the pipelines that transport tar sands oil into the US.

According to an EEI research paper by Jennifer Huseman and Damien Short:

large-scale resource extraction not only alienates Native peoples from their land by driving them off of it in order to make room for industrial activities, but also by way of the concomitant toxic by-products that put water supplies, land cover, and wildlife at serious risk; thereby gravely jeopardizing the lives, cultures, and health of indigenous communities who depend on these resources for their continued existence.

In addition to the threat to their traditional way of life, the indigenous groups living in tar sands areas experience higher incidents of cancer, including incredibly rare forms of the disease.

Transporting tar sands oil, also known as diluted bitumen, is much more difficult than transporting traditional crude oil. Due to its thick consistency, it will not move through a pipeline on its own and must first be diluted with a wide range of chemicals, some of which are toxic. When the pipelines transporting it fail and the diluted bitumen and other chemicals spill, which has happened several times along pipelines in the US, local communities are devastated and it is almost impossible to clean up. It does not float like traditional crude; instead tar sands oil sinks to the bottom of rivers and lakes. People living in areas that have experienced a spill report many health problems as well as an inability to sell their homes.

The majority of environmental and human rights activists agree that the tar sands in Canada are the ‘most destructive industrial project on earth’, yet there is much more debate about fracking. Having seen a boom in the US since the late 2000s, the extraction of shale gas through hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, has caught the attention of the world with many countries, such as the UK, Poland, and Argentina, attempting to create their own shale gas industry. And while much of the debate around fracking is related to the potential contamination of water, there are also concerns about air pollution caused by the wells as well as the noise emitted by the 40,000 horsepower diesel pumps used at the well sites and the damage to local scenery. Small Global: Extreme Energy includes a photographic map of planned fracking sites all over the world – some of which are surprising – and the EEI is currently researching the potential impacts of fracking on communities in the UK, based on data gathered from sites in the US and Australia.

What is clear from our preliminary research is that extreme energy (and climate change) will somehow touch us all, and we are delighted to be collaborating with artists and Greenpeace to bring our public engagement project to such a large audience. With thanks to funding from SAS and Arts Council England.

If you make it out to Glastonbury next week, be sure to go by the Greenpeace field and experience Small Global: Extreme Energy. It will be showing in the CLiMAX dome on Saturday, 28 June from 14:00 to 17:00. On Saturday, there will also be a projection of the project on the outside of the dome from 23:30 – 1:00.

No comments yet