We see through the eyes of the artist

My friend Feargus sent me a letter in response to the AR Manifesto. The letter gives me an opportunity to give a practical example of how art shows us the world. (scroll down to letter)

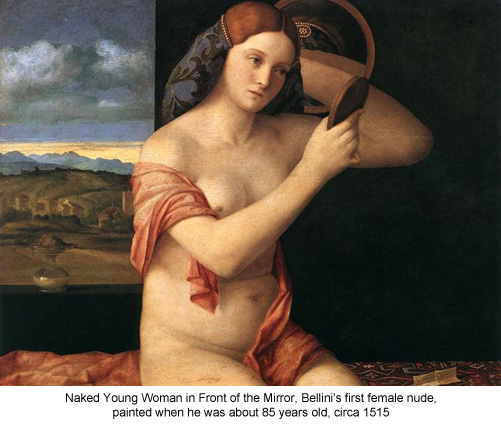

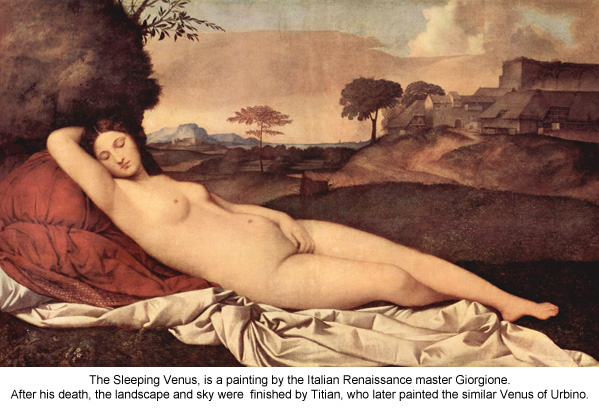

We went to Florence for an exhibition of the African bags before going on to the menswear show in Milan. Andreas managed to squeeze in a visit to the Uffizi in Florence. When he returned, he talked of Titian and his painting the ‘Venus of Urbino’:

“This painting is the painting of all time; it says everything. There is nothing before it and nothing after it.

“The idea is that there is no idea – just this woman – it doesn’t mean anything. For the first time in painting, she’s not Diana, she’s not Eve, she’s not Judith; she’s not Venus (the title ‘Venus’ has been given to her later): she’s an image of life. This image of life, it had to be a woman – the woman gives birth; no, it couldn’t have been a man, a man can’t just cover his cock with his hand.

“What’s it all about?” (Meaning we are all interested in her.) “We all know it; it’s mesmerizing.

“Manet’s ‘Olympia’ is very similar. They are the same. Manet is more direct; Titian is more stylised.

“Its sfumato is the finest sfumato ever. It’s not lit, not diffused; not clear, not blurred; not real, not fake: it’s in perfect equilibrium. It’s a world you think you know, yet it’s invented.”

(Vivienne: Andreas, you said that the impact of Renaissance painting is full of colour but when you came to the room with the Titian, it was all one colour.)

“I can never understand the colour: there is hardly any; it’s the way it’s put together, the weight of it. It’s not the real world, yet it seems to reflect it more than anything.”

(Vivienne: I think we all search all for perfection and truth, as well as outlook on life. Sorry, I know generalizations don’t interest you.)

“Well, Titian is known as ‘the painter of the poesie’.”

(Vivienne: What do you think of Feargus’ dog (see letter).

“The important thing is that there is a dog! It’s the woman’s companion – a King Charles spaniel, a pet. It’s part of the subject matter. It would be a horrible painting without it.

“And the hairstyle! (Andreas’ hand over his own head follows the shape of the plaited crown.) And the way it comes down on her, into her neck. There is nothing like it. And she’s holding the violets.”

(Vivienne: And the two servants, getting her clothes from the chest?)

“The painting is talking. What will happen next, what is she up to?”

(Vivienne: That’s what we mean by ‘the painter of the poesie’. Poetry tells a story – reduced to its essentials; you get the idea in one go. The detail helps – the universal in the particular. But of course it’s the way it’s done that makes it – that’s the mystery.)

Andreas is a visual person: he understands everything from what he sees. He has obviously entered the world that Titian has created and can look into it and also out of it. This illustrates my point in the AR Manifesto that each work of art is a window on the world, an artist’s view, throughout time, which we can concentrate into our own experience.

Let’s carry on talking about Titian and his Venus. What else do I get? Let’s try to pin down further the comparisons art gives us and which help us understand our world:

Most important: There once lived on this earth a man, Titian, who developed his gigantic talent to an extreme which still seems to go beyond the limits of human potential. Even so, such an event cannot just happen: the man must take advantage of the situation. Others must prepare the way. It has to be a culmination; the result of skills developed and built up over generations.

This was the time of the Renaissance and men were inspired by the Greek genius to push themselves to the limits. The world opened to new ideas. Imagine! Such a painting couldn’t exist in a world held close by religious dogma.

So, what we’re saying is that the time had to be ripe for Titian; ready for him to express his genius. That is why the art lover is so important; in other words, we get the art we deserve.

Renaissance society was an intimate one, everyone knew everyone in their group. It was dominated by guilds of craftsmen. There was a greater proportion of intellectuals per capita than in our age, and a greater respect for learning and contemplation. Titian was feted for his talent and given every privilege.

The past window on the world I have just described is a combination of historical facts and appreciation of art which we continue to adjust and develop from more facts. These facts are in turn illuminated by knowledge of art.

-Feargus’ letter-

A Response to the Manifesto

I remember reading the early drafts of the manifesto and have for a long time followed its progression into the work that it is today. From the first time I read it until now, there has always been something about its message that I felt was truly important. There was something that struck a cord and left a lasting impression that has stayed with me for years. I have often sat down and contemplated the message, trying to understand why it left such a strong mark and have finally come to some conclusions. Moreover, I have often considered how this document translates from being a piece of literature into a way of living i.e. the practical implications of the idea.

My own conclusion, and this is for anyone to disagree with can be summarised in one small acronym CACA, standing for Culture, Analysis, Criticism and Action, each of which I now hope to expand on.

Culture

The underlying thesis of the work is that the future of our planet, our very existence is dependent on the continuing development of our sense of culture. While the notion of ‘being cultured’ has a ring of elitism and old fashionedness about it, culture for everybody is in fact a very revolutionary concept. Through out the history of humanity there has never been any major change to our civilisation without it being preceded by a burst in cultural awareness and growth. All one needs to do is look at the Enlightenment, Renaissance, Greek Civilisation, the Egyptian civilisation, the Iraq, South American and others, all of which have not only left their marks on the world vis-à-vis scientific, architectural and medical developments but have also left an indelible cultural mark on the psyche of human society. It is hardly coincidence that all of these revolutionary developments run parallel with growth in our cultural insights.

It seems a pity that so many think of culture as a middle class hobby, something that the rich do on the weekend, such as go to the gallery or see a play. In fact, this sense of cultural elitism is only a recent phenomenon that never really existed prior to the advent of Television. It is a sad irony that despite the fact that more people can do more things then ever before in our history that fewer consider their own cultural development as a fundamental part of their existence. In the old days, few were educated and few could read.

Culture was the preserve of privileged and powerful people: Greek culture was only for male citizens, though it was imposed on everyone through aesthetic and ethics, e.g. architecture, statues, religion; also social mores and we might add dress codes. The mediaeval church provides a very strong example of this.

During the 18th century, the idea of universal education began to take hold, following on from the wish to extend the franchise, eliminating privilege. During the 19th century, reading had become very important to the working man. He viewed education and culture as a necessary means towards empowerment, social status and democracy.

From the impoverished East-end of London, the tribal villages in Africa, the peasants’ fields in Russia and so on, plays, art and literature were instrumental in everyday life. Farmers and machinists would go to a play or look at the pictures in pamphlets or have the only reader in the village read to them and this is where revolution was born. Yet, today more and more people can read and write but there is less and less interest in culture. Maybe that is more an indictment of our educational systems then anything else, the fact that illiterate farmers and miners cared more culture we do today, must raise some questions of our educational institutions. How can somebody go through 12 years of an institution of learning and have never been exposed to Durer, Brecht, Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Russell etc. Why is the only thing that is not a priority in school the only thing that can really change the world, namely culture? Is it really that dangerous, that much of a threat to the status quo that over the past century it has all but been eliminated from our schools?

My impression today, is that a modern education teaches you how to consume and not to how to think. We are fed the information day by day, learn this, learn that and you will pass your exams. Don’t answer the question with any imagination, that would be too risky, don’t try to be original you don’t know enough…. . Once you pass then off you go for more of the same thing at university and then eventually you can get a good job if you’re lucky. If you know how to consume the information you will get a job. Not if you learn how to process the information and develop an idea, quite the opposite, in fact the antithesis of education. Again, referring to a day gone by, students learned Latin, Greek, history, French, geography and science. With that they learned by discussion and by being trained to develop their own opinion on matters, but it was more important to think about the fact than to repeat it. In some ways it is this lack of education in the most educated civilisation that has alienated us from culture. We are fooled into thinking that because we can read or write we have overcome the ignorance of the past, whereas even in feudal times what little the peasant did know was focused on the world he lived in – everything was pointed at highlighting the world they lived in as it was, while at the same time pointing out how the world should be. Today, we know a lot but it amounts to nothing, because we don’t know what to do with the information, thus rendering it valueless.

In my opinion the greatest coup of the 20th century was to make people feel like being cultured was a boring, almost dirty thing to be, when in fact it is the stuff of revolutions, but then again, that is probably the very reason why.

In the last paragraph of ‘On Liberty’, J.S. Mill states,

…a State, which dwarfs (the minds of) its men, in order that they may be more docile instruments in its hands even for beneficial purposes, will find that with small men no great thing can really be accomplished…

Analysis

Culture is not an end in itself, it is the consequences of culture that brings about the change, this is why it is so important for those who control the zeitgeist to de-culture society. It is in my mind quite simple; culture leads to analysis, which in turn has its own repercussions. It is like a chain reaction that once started can’t be stopped.

When we see an image, go to a play or read something new, there comes a point when we have to think about it. We learn to discriminate because we begin to analyse what we read or see, especially the more we are exposed to those elements. The analysis is a natural process by which we take the story on its face value and look beneath for the message or the question being asked of us. Often paintings and stories are not overt or explicit in what they say about the world we live in and the viewer is required to seek meaning. A great example of this is Renaissance paintings; they are full of messages and symbols that are designed to speak to the viewer beyond just the picture. They reflect the socio political circumstance of their their time and reflect how things ought to be.

Yet today we are faced with unmade beds, cut up sharks and Big Brother. There is supposed to be a genre of realism in all of this, but in fact it is as about unrealistic as it gets. If there is any reality in it, it is only to expose how truly far our society has slipped into a cultural vacuum, leaving us with nothing to analyse, no statement as to how the world is, nothing to evoke a vision of the future, designed only to shock and provoke baseless and meaningless conversations. What good does that serve as art, when its effect is to contribute to the debasement of what culture is. It is as though the norms of culture are being shifted and that somehow or another this is what those in the know now call culture when in fact all that we learn from it is maybe something about what the artist was feeling.

This process of analysis that is the consequence of culture is essential for the progression of civilisation because it teaches us to see the world with fresh eyes and to actually think, rather then just to consume the image. Durer, Shakespeare and all the other greats knew that their work would be analysed by its viewers, they understood that people would look behind the veil to understand what it is that the artist was trying to tell them about the time they were in. Sometimes it was to convey current affairs, to suggest a way forward or to express dissatisfaction at some decision that was made, but always in the front of their mind was the knowledge that ordinary people would be analysing every aspect, wondering why did he use Hector or refer to Hannibal or paint a ship of bishops and call it the ship of folly.

It is this very notion of analysis that leads onto the next event that results from culture and being cultured which is criticism.

Criticism

Once the analysis begins it is at that point that people become critical. The observers of culture will look to the art and determine if they agree or don’t agree with the message. Discussions would follow, did you hear that part, did you see this….. , and from that people would understand its symbolic meaning i.e. a dog with a crown could be a reference to the fact that the king or queen was strong and loyal, but then if the dog is at the feet or under the table of another person it could be to suggest that the monarch is subservient to somebody else. No doubt this conclusion would bring about further conversations as to whether or not people agreed with that analysis and it is this kind of criticism that culture evokes.

We learn from culture to be critical of our environment and those who dominate it. We begin to understand the impact of decisions being made on our behalf and by being able to analyse those decisions we can determine for ourselves whether or not it is the right decision. Of course this is quite naturally a dangerous proposition for those who make the decisions. The comfort of power would much rather that we accept the decision as being made for our best interest and like with everything else we consume we should consume their justifications without thinking. Why would anybody in authority want us to be cultured when they are saved from our rebuke?

The fact is that without culture there can never be a revolution because there can never be analysis and therefore criticism, without which there could be no action.

Action

The final element speaks for itself. Criticism leads to action. Once people begin to understand and be critical of decisions then eventually they will act upon it. Nothing can hold back this action because it becomes embedded in the zeitgeist of its time, it cannot be controlled or dissuaded once formed. Action is what revolution is.

Conclusion

How can culture save the world? I think it is quite straight forward. From cultural awareness we can begin to analyse the current state of affairs, we can begin to see the nature of our behaviour and understand its consequences. From that we can begin to become critical of those decisions that have created the problem, realising that it is not a road that we wish to walk down and consequently we can choose to change direction.

(Vivienne’s reply)

I’m really impressed and delighted that you’ve give so much thought to the Manifesto, Feargus. I really value your letter. You’ve really put your finger on the practical application of the Manifesto with CACA.

I agree that culture makes us question our values and stimulates us to think how we can make the world a better place – and yes, ideas can be revolutionary. But I don’t believe in violent revolution which has always caused more harm than good – I include the French Revolution.

Feargus, when you reach the part about Analysis which leads to Criticism, I don’t agree that what we’re looking for is the message below the surface. You give the example that a dog in a painting might be a coded political symbol. Of course, satire has its particular place in culture and political art is legitimate but art doesn’t need to be didactic (Whistler, “Art has no wish to teach.” The founding principle of ‘L’art pour l’art’ is that art has no message; art exists.)

Criticism and discussion are part of culture. Appreciation of art is up to us; as the True Poet says in the AR Manifesto, “We see through the eyes of artists who lived before us, all those very different views of the world throughout time, which we concentrate into our own existence: knowledge of life through an artist’s knowledge of life.”

Excellent post, Vivienne. Thank you for posting Feargus’ letter and your response.

I do agree with you that while ideas can be revolutionary, violent revolution is often detrimental to a society. Just look at the revolutions in Middle Eastern countries for example, where museums are looted and destroyed and valuable artifacts are stolen or lost during the process of overthrowing those in power. I worry about the current state of things in countries like Egypt where culture and archeological discovery is threatened by an uncertain government and threat of religious dogma being imposed on their society. I think we have to be very careful when we say we support “freedom and democracy” at the expense of stability and culture.

Best Regards,

Jeffrey Jordan

Comment by Jeffrey Jordan on 27/06/2011 at 4:29 pm