Pooh sticks, pauses and predictability

Guest blog by Prof Richard Betts

Two new scientific papers [1,2] may help explain the recent temporary slow-down in global warming. The average temperature of the Earth’s surface has not risen so fast in recent years, and the new research adds to other studies which suggest that this ‘hiatus’ or ‘pause’ is largely due to natural climate variability – basically weather – with possibly an additional small cooling influence of the sun and pollution particles partly offsetting the warming due to greenhouse gases. One of the new studies suggests that heat has been building up deep in the Atlantic and Southern oceans instead of warming the surface, and previous work has suggested similar heat build-up deep in the Pacific – which means that the world as a whole is still heating up, even if we’re not seeing so much of this at the surface just at the moment.

The ‘pause’ does not mean that climate change has gone away, but it does highlight the challenges in forecasting climate on the short timescale of a few years. While in the long term, putting more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere will inevitably cause the planet to continue to warm, in the shorter term the effects of natural climate variability tend to dominate. These are inherently harder to predict. Critics of climate science make much of the fact that the ‘pause’ was not specifically predicted in advance – even though longer-term warming was successfully predicted in the early 1970s [3], and the current pause is still within the uncertainty bounds of the climate models [4].

However, just because short-term forecasts are hard to make, this does not mean that we can say nothing about the long-term effects of pushing the climate system by altering its radiation balance with more greenhouse gases. There are two things at work here, one largely random (or at least, so complex and chaotic that it appears random), and another which is a movement in one general direction due to being pushed from outside. The first is hard to predict, the second less so.

It’s rather like the flow of a river, which has its long-term direction set by a well-known law of physics (gravity). Rivers flow downhill. However, within that flow in one direction, there are swirls and eddies where individual areas of water are moving faster or slower, or even temporarily back upstream. But ultimately, all the water generally flows downhill.

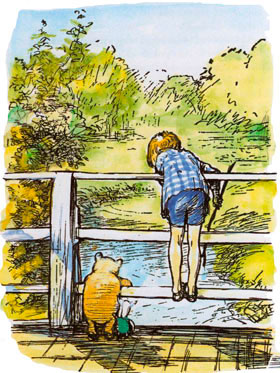

Think of the game of Pooh Sticks. This works as a bit of fun because it’s partly predictable and partly random – you know that when you and your friends drop your sticks off one side of the bridge, and run over the other side, you’ll see the sticks coming out from underneath as they are carried down the river. But you don’t know which one will come first, because of swirls in the water making some go slightly faster and some slightly slower. The first part – rivers in one direction – is like the long-term climate change problem. Rivers flowing downhill and the climate warming because of higher greenhouse gas concentrations are predictable in general because of well-understood physics. The second part – sticks being carried at different rates in different parts of the river – is like the problem of trying to predict specific years or seasons. The influence of gravity or greenhouse forcing is only factor among many others, including the fact that detailed river motions and the weather are essentially chaotic which makes the details hard to predict.

Claiming that long-term warming won’t happen because the ‘pause’ was not specifically predicted is like saying that you can’t be sure the river will flow downhill because you can’t predict the winner at pooh sticks.

[1] http://www.sciencemag.org/content/345/6199/897

[2] http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ngeo2228.html

[3] http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~eps5/writing_assignment/CLIMATE_BKGD/Sawyer_Nature_1972.pdf

[4] http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_Chapter01_FINAL.pdf (Figure 1.4)

Prof Richard Betts is Chair in Climate Impacts at the University of Exeter, Head of Climate Impacts Research at the Met Office Hadley Centre, and coordinator of a a major EU-funded international climate research project ‘HELIX’ (High-End cLimate Impacts and eXtremes) http://helixclimate.eu/home

So as gravity is the strongest force acting upon the river so GHG’s are on the atmosphere. Wonderful, no more ice ages is what I think you are predicting from this as I can’t think of any analogy that would force the river to flow uphill!

Comment by Lord Beaverbrook on 03/09/2014 at 12:40 pm

I am genuinely shocked that any adult human being would lie as scurrilously as that.

Come back in 200 years and the models still won’t work and there will be cheeky rascals like Betts making half witted excuses.

Comment by Eric Mcoo on 03/09/2014 at 9:07 pm

At the exact point when a bunch of self serving modelling technicians predict the end of the world, excess heat suddenly transfers from the air to the oceans.

It’s as if when Galileo dropped the balls from the leaning tower of Pisa, they arrived on the ground simultaneously for the first time. Millions of scientists round the world thought ‘funny, it didn’t do that yesterday, the heavy one landed first’.

Comment by Eric Mcoo on 03/09/2014 at 9:14 pm

Wish scientists were more open on revealing the incredible challenges that accompany climate forecasting at spatial level just as explained by Betts wrt the temporal side. Global climate change is at the moment pretty much impossible to downscale at continental let alone national level, for the same reasons yearly variability can mask the expected long term trend. Andyet we see every reports stating what this or that region will experience. That’s not science.

Comment by Maurizio Morabito on 03/09/2014 at 9:15 pm

Apologies for the mistyped end. “And yet we see every DAY reports…”

Comment by Maurizio Morabito on 03/09/2014 at 9:16 pm

[…] finish this post by mentioning a relevant article by Richard Betts on Climate Revolution called Pooh sticks, pauses, and predictability. It’s a good post, and it reminded me that – at university – we had a student […]

Pingback by The “pause” that probably isn’t | …and Then There's Physics on 05/09/2014 at 8:05 pm

Lord B, there is nothing about GHGs being the strongest force. Youmade that up.

Eric Mcoo, please identify a ‘lie’ in the text.

Maurizio M, do we really see scientific papers that are so unequivocal, or is are they couched in probabilities and confidence intervals? Is it perhaps the reporting of the science that translates interesting modeling results into certainty?

Comment by Raff on 06/09/2014 at 2:28 am

Raff,

Thanks for your points – all well made.

Eric,

You don’t do sceptics any favours by bandying about strong words like ‘lie’ without substantiation. If you want to disagree then that’s absolutely fine, but you’ll have far more credibility if you take a leaf out of Lord Beaverbrook’s book and do so calmly and rationally instead of spitting hate.

Comment by Richard Betts on 06/09/2014 at 11:45 am

Also, I can recommend the blog pinged back in comment 6,‘And Then There’s Physics’ for further interesting discussion of climate science and matters arising.

Comment by Richard Betts on 06/09/2014 at 11:48 am

[…] that you can’t be sure the river will flow downhill because you can’t predict the winner at pooh sticks (H/T Richard […]

Pingback by A real Hiatus | …and Then There's Physics on 16/09/2014 at 6:55 pm